There are some people who nap in response to sleep loss. This is called replacement napping. If you only got 4 hours of sleep last night, then you may nap to replace that loss. That might not work but more on that later. There are other people who nap to prepare for sleep loss. This is called prophylactic napping. If you know you’re only going to get 4 hours of sleep, so you nap in preparation for that loss. That might work, but again more on that later. And there are others who nap for enjoyment. This is called appetitive napping [1]. If you nap because you have absolutely nothing better going on in your life. Then you’re just lazy. Just kidding, I’m 30 so I don’t judge people anymore. Nap away! But no matter your reason, does regular napping have evidence-based benefits? What is the optimal nap duration and time of day? And why don’t I nap? Well, let’s get into it!

Napping Benefits

If you look into the studies researching napping, you’ll see a lot of confusing associations. Daytime napping is associated with increased obesity or type 2 diabetes [2] or even increased inflammation [3]. Oppositely, you’ll see studies showing that daytime napping can facilitate successful aging by preventing disease and increasing cognitive function [4]. As I’ve mentioned before, these association studies are deceiving because the direction of the relationship isn’t always understood [3]. Does napping lead to diabetes, obesity, and chronic inflammation or do people with diabetes, obesity, and chronic inflammation nap more in response? You just don’t know unless you perform and analyze intervention-based studies. To which this is much more difficult but here are the benefits I did find.

Napping does appear to improve mood and subjective levels of sleepiness and fatigue. And it can be particularly beneficial to performance on tasks, such as addition, logical reasoning, reaction time, and symbol recognition [1]. In one study, they had participants either take a 90-minute daytime nap or an equal interval of quiet wakefulness. They then had all the participants study a list of words: green words to remember and red words to forget. After that, they quizzed the participants on these words and found that the recently napped participants had improved episodic memory retention [5]. But these longer naps (e.g., sleeping for 30 min or longer) produced sleep inertia, making nap benefits obvious only after a delay [1]. So, what does your sleep architecture look like and what is this thing called sleep inertia?

Sleep Architecture and Inertia

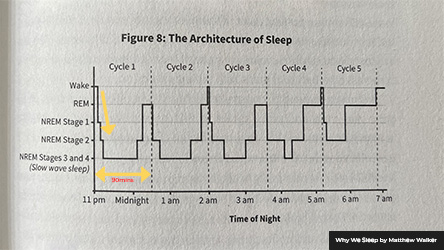

Sleep inertia is characterized by a reduction in the ability to think and perform upon awakening due to sleep. It’s that feeling of confusion and grogginess, where you can’t even remember what day or time it is. Is it my birthday again? Nope… But sleep inertia is associated with longer naps as it is typically thought to result from awakening from slow wave sleep. For example, a 10-min nap for most won’t show any sleep inertia effects while a 30-min nap will [1]. This is because the average sleep cycle is 90 minutes long. And over those first 30 minutes, you’ll slowly dive from a state of wakefulness, into REM sleep, and then NREM Stage 1 to NREM Stage 2, all the way down to deep NREM Stage 3 and 4 sleep. And the further you fall into this deep sleep cycle, the more inertia you’ll feel upon wakening. That’s why it’s best to stick to shorter naps, 20 minutes or less, so that sleep inertia is suppressed [6]. Or wait until your full sleep cycle completes around the 90-minute mark. Now that we understand our sleep architecture, what is the optimal nap time and duration?

Optimal Nap Time and Duration

In one study, that’s results appear to agree with many other studies, a mid-afternoon nap was more recuperative than a nap taken at any other time during the day, for example, at early morning, at noon, and at early evening. These mid-afternoon naps occurred between 1 and 4pm where your circadian rhythm naturally raises your sleepiness. You’ll feel this sleepiness even if you skip lunch or had adequate sleep the night before [7]. Its code built into your system and why car accidents rise during this period while your alertness drops [8]. This 1-4 timeframe has been deemed the ‘sleep gate.’ Open the sleep gate! Napping during this time improves sleep efficiency, shortens sleep latency, and produces greater amounts of slow wave deep sleep if you nap long enough (beyond that 30-minute mark). Outside of this period, napping not only may have less benefits but could have negative side effects. So, if you miss the golden sleep gate, you’ll want to avoid the evening forbidden zone between 7 and 9pm [1]. I forbid you to nap in this zone! Who comes up with these names? These later evening naps can disrupt your regular sleep quantity and quality which I’ll touch on in a bit. But most studies seemed to indicate that naps after 4pm should be avoided [9].

As far as optimal nap duration, a 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-min nap, as well as no nap, were used to determine if brief naps were as effective as longer naps. They showed that the 10-, 20-, and 30-min naps produced improvements in cognitive performance and alertness, while the 5-min nap and no nap conditions did not. Moreover, the 10-min nap showed immediate benefits, while the 20- and 30-min naps led initially to sleep inertia but then produced benefits after the inertia subsided. But, three hours post-nap, there were no differences among all five conditions [1]. Now, longer naps around the 90-minute mark could have extra benefits compared to shorter naps because you’re diving into those deep sleep stages. Either way, a 10–20-minute regular nap between 1 and 4pm seemed to be optimal and if you have time for 90 minutes, there could be extra benefits to that too.

Why I Don’t Nap

But despite my findings and attempts at regular naps, I rarely do it anymore. First, the outcomes of napping on performance and health are a little mixed. Although the immediate results of napping can be positive (e.g., improved motor and cognitive function, reduced fatigue), these positive results are not long lasting and seem to dissipate after a couple of hours. In no way does a nap replace a good night’s sleep. Second, excessive daytime napping can have a negative impact on the quality and quantity of nighttime sleep and give rise to a cycle of poor sleep [10]. And this is what has affected me the most.

Throughout the day, as you’re awake and expending energy, you build up a chemical in your brain called adenosine. Adenosine can be thought of as a pressure to sleep. And as that balloon or pressure expands throughout your waking hours, the more pressure you’ll feel to sleep. Then at night, once you get that nice long bout of high-quality sleep, the balloon deflates again by the morning and the process starts all over. But taking naps can relieve some of this sleep pressure. Then at night, you might not have that same pressure to sleep making it more difficult to fall and stay asleep [11]. This is definitely what’ve experienced and can lead to a poor night’s sleep. Which can then make you more likely to nap the next day and the cycle continues. Instead, I do my best to stay awake throughout the day and focus on getting one bout of high-quality sleep at night.

Final Thoughts

The optimal nap depends on many factors that I didn’t cover like individual sleep need, timing of sleep/wake schedule, morningness-eveningness tendencies, quality of sleep during the preceding night, quality of sleep during the nap, and amount of prior wakefulness. And the benefits of naps will depend on these factors [1]. But for most adults interested in regular napping to reduce fatigue and boost performance, a 10–20-minute nap between 1 and 4pm appears best. But for me, I avoid naps because they decrease my pressure to sleep at night making it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep.